Are you managing risks or managing outrage?

By treating people as human we stand a chance of reducing their level of outrage, which is likely to reduce their sense of the risk.

I have recently had cause to delve back into the world of risk communication, where I was reminded of a couple of fundamental pieces of work that continue to feel relevant, even as the world seems to be filling up with outraged people.

The Factors That Contribute to a Perception of Risk

The first idea is that there is only a low correlation between the actual level of physical risk in a situation and the amount of concern it generates. Dr Peter Sandman and Dr Vince Covello have done a lot of work in this area over the years. They offer a list of factors that contribute to our perception of risk, including things like perception of fairness, novelty or knowability, control or lack of control, emotional impact, visible v invisible etc.

A key point for me is that as the proponent of a project or a change it is easy for me to 'know' the risk is low. But this bears no relationship to how risky it feels to others. If I feel like an innocent bystander subject to something I don’t want, it is hard for me to see this thing as anything other than risky, with lots of negative consequences. At which point I create the Facebook page.

Regardless of the actual risks posed, if a proposal ticks some of these boxes the project feels risky, which amounts to the same thing as far as stakeholder outrage goes. Which of the factors might your projects be tapping into?

This idea is neatly expressed in Dr Peter Sandman's famous equation: Perception of risk = hazard x outrage.

In other words my sense of the danger something presents is driven by how upset I am about it, rather than the other way around. While it always seems clear to me that my outrage reflects a rational assessment of the actual risks involved, Sandman shows us that the extent to which I think something is risky is largely driven by my level of emotional engagement. If I'm upset I think it's dangerous. If I'm not upset, I think it's safe.

Managing Risk Perception

These ideas from the risk comms world give us a strong clue about how to respond to an outraged community and it isn’t to present all the facts about why the project isn’t dangerous. Instead we must treat the outrage, rather than downplay the risk. This means listening, admitting negative impacts where there will be negative impacts, walking in their shoes and seeking to understand their perspective. Being vulnerable. Even apologising if that’s relevant.

By treating people as human we stand a chance of reducing their level of outrage, which is likely to reduce their sense of the risk.

Sound risky? Perhaps that’s our emotional response talking.

Vote 'Yes' to Listening and Curiosity

Vote 1 Polarisation

In Australia we are deep in the public ‘debate’ about the upcoming referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution. In the national media at least it tends to be less a debate and more a noisy process of defending one’s own opinions and deriding the others’.

The unseemly nature of the public discourse is perhaps inevitable given that we are looking at raw politics at play. But even without the political nature of the discussion a referendum is always polarising because it forces a binary choice. Yes or no. Support or don’t support. I am right, which means you must be wrong.

The dynamic that is forcing Australians into one of two camps – pro or con - comes at a cost to our national harmony. It’s also a great example of what to avoid when working with diverse stakeholders on complex issues, because binary debates are not only overly simplistic, they always force people further apart.

When I work to convince you of why I am right, while at the same time refuting your attempts to do the same, we can’t help but become further entrenched in our own positions. The distance between us can only grow, and we each become even more ‘wrong’ in the eyes of the other.

How to get unstuck

What can we do about it? When in this situation we need to reverse the polarising nature of the discussion, and find ways to talk that bring us closer together rather than drive us apart. Ultimately we want them to be curious about our ideas and perspectives, but this can be challenging because in order to do this we probably first need to be curious about and interested in their ideas and perspectives. That is, we need to:

- Stop talking and start listening.

- Be authentically curious about what they are saying and why.

- Help them articulate their position more clearly.

- Be genuinely open-minded.

Then perhaps they will start to explore our opinion.

When collaborating, don’t set up situations that become referendums on the question at hand. Rather, set up conversations full of exploration and learning. That’s how we make progress together on complex issues. I vote yes to that.

Down with Difficult Debates

“We need to have a difficult conversation with them”.

So said my client the other day when discussing their relationship with one of their key external stakeholders. And as they said it I could almost feel the tension in the air as they pondered that conversation. It felt difficult. It felt unpleasant. It felt dangerous.

Since the meeting I’ve been wondering why conversations that go a little deeper, that share a little more honestly, are seen to be ‘difficult’. I’d like my clients to see these situations as opportunities for learning, but it seems that we are all so entrenched in the model of debate and argument, winning and losing, wrong and right, that we can only see these discussions as adversarial.

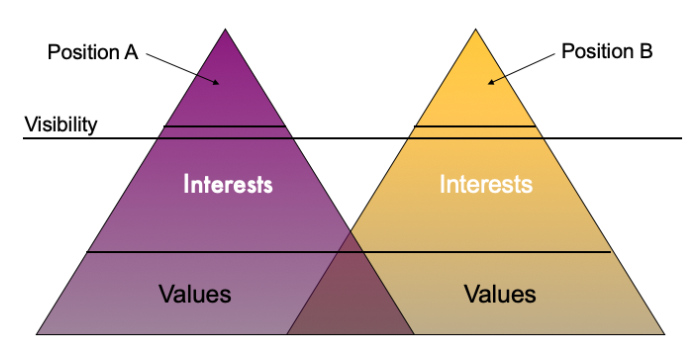

I often turn to our simple ‘Values Triangles’ framework to help make this dynamic visible for clients. It depicts two people, person A and person B, each with a strongly held ‘position’ or idea. We can see that between the two positions there is a space - the distance between us. And our adversarial thinking tells us that, when confronted with an opposing idea, our task is to argue our case and convince them that our position is the right one. The space between us grows. We become more entrenched and polarised in our views.

The framework also shows us that our positions are supported by interests, the reasons we think this is best, which in turn are supported by our values, our fundamental beliefs and things we hold to be important. It also illustrates that different positions can be supported by similar interests and values, and that we are likely to have more in common than we first think.

When my client is imagining a difficult conversation, I suspect they are imagining being stuck at the top of the triangles, having an argument about right and wrong. Difficult? Yes. Inevitable? Definitely no.

With a different mental model, one based around learning, curiosity, exploration and relationship building, we can have these conversations differently. We can explore each other’s interests and values. We can together create alternative positions.

With some simple skills and processes we can get out of our adversarial thinking and start learning together about what makes each of us tick. That’s an interesting conversation rather than a difficult one.

Failing to Reach the Summit of Collaboration

Remember Kevin Rudd’s Australia 2020 summit, billed at the time as a people’s forum to help “shape a long-term strategy for the nation’s future”. It was 2008. Rudd was a new and exciting Prime Minister who appeared determined to shake things up. The Summit looked like clear evidence that this government would do things differently, that here was a government that listened, led by a PM who wanted to bring us all on the journey.

The Summit was a very high-profile event, with 1000 delegates selected from across Australian society. Actors and other famous types were hand-picked to chair 10 working groups, each of 100 people. It was a big deal, an enormous event and a huge logistical undertaking, a massive investment in doing government differently. It looked like this government was actually trying to collaborate with us, the people. It was exciting.

Over two days Australia’s ‘best and brightest’ rolled their sleeves up and got stuck into some big and difficult issues. There was enough flip chart paper and sticky notes to sink a ship. At the end of the summit there were speeches and everyone went home exhausted, having done their best to nut out some hard problems.

A final report from the summit was handed down. 135 of the 138 recommendations were rejected.

And this is the difference between doing collaboration and being collaborative. To do collaboration was to get 1000 people in the room and ask them to come up with recommendations. Easy. But being collaborative, thinking like a collaborator, the PM would have recognised that:

- Authentically tackling complex problems requires investment in relationships, which in turn requires time and space for conversation.

- Learning is at the core of useful collaboration, and with it, the disagreement, challenge, exploration, joint fact finding and coming together that demonstrate we have learned from and about each other.

- Letting go of control and releasing power are essential to authentic collaboration. Micro-management of issues and scopes and information and messaging are anathema.

- Making decisions about the merit of recommendations is a key part of any collaboration. Do this with not to stakeholders.

- Genuine diversity of opinion is essential. Handpicking the ‘best and brightest’ is to impose my views on the event.

I believe the PM and his government were genuinely trying to do something different. But, as is often the case, they invested hugely in the doing without making the same effort in the being. And if there is one thing I have learned over the years, it is that being collaborative trumps doing it every time. When we think like collaborators we stand a good chance of authentically collaborating. The reverse is much less true.

So are you both doing collaboration and being collaborative?

Do Be Do Be Do Collaboration

To do is to be (Kant)

To be is to do (Neitsche)

Do be do be do (Sinatra)

So goes the undergraduate joke. But whatever these three famous philosophers may or may not have said, the joke reveals something important about collaboration. To be a collaborator requires us to do collaboration. And to do collaboration we must be collaborative.

Or to put it another way, authentic collaboration requires us to both think and act like a collaborator.

So far so obvious. And yet I see many organisations professing to do collaboration without having recognised the requirement to be different. And so they:

- Get their stakeholders in the room but retain control over key aspects of the conversation, such as the scope, the problem to be solved, who is invited, what data are relevant, who’s voice is heard, and so on.

- Ask for feedback in the name of collaboration, when they are more accurately consulting.

- Reserve the right to ignore or downplay collective decisions.

- Send the (often mostly female) customer engagement team out to ‘collaborate’, while retaining decision-making powers within the (often mostly male) 'core Divisions' of the business.

Authentic collaboration requires a shift in mindset as much as it does a shift in practice. Or to paraphrase our three philosophers: Real collaboration with real people on real problems requires us to do and be and do and be and do collaboration.

So does your organisation strive to be collaborative in order to do collaboration?

Isn't it great that we disagree?

Why disagreement and divergent views are the essential raw material of collaboration, to be embraced, acknowledged, even celebrated.

Recently I was involved in a project to find a solution to a challenging policy question. While running a workshop with stakeholders I did what I often do and asked each of the 40 people in the room to write down on a sticky note what they think is the problem to be solved by this policy. As is always the case, within 10 minutes we had 40 quite different views of the problem (and some 'solutions') on the wall for all to see. We went to a lunch break and the client came up to me and said something like “that's the problem. Everyone has a different opinion and we can never agree on anything!”.

Back in the workshop after lunch it was clear that the client’s view was widely shared. We disagree! We will never get alignment! This collaboration thing is doomed!

I understand this view, but I believe that the much bigger problem is that we see these differences as the problem. Because I’ve learnt that the 40 different views in the room are the raw material from which a great outcome will be generated.

As usual, my message to collaborators at this point is “isn’t it great that we all see this differently”. And I genuinely believe this for a number of reasons:

- Different opinions decrease the likelihood of ‘group think’ while making something novel more likely to emerge.

- The more differently we see this situation the more likely it is that we are capturing the bulk of relevant issues and concerns and opportunities. If we see things in a narrow way we are probably missing some important stuff.

- The fact that we see the situation differently makes working together more important. In other words, it builds the argument for more collaboration, not less.

- Inviting the difference helps us all see that we have a place in the discussion, that our views and experiences are relevant, even essential as part of the full picture.

- Acknowledging differences and working with them is a great way to build trust among collaborators. Listening across differences helps to build relationships.

So, the next time your collaborators express differences of opinion and are seeing things differently, you can feel ok to step into that difference and draw on it to create something that none could have thought of alone.

The Computer on Mindsets

I have always felt that a collaborative mindset is fundamental to authentic collaboration, but what does ChatGPT say about it? Here's its unedited response to the question: Why is mindset important for successful collaboration?

Mindset is crucial for successful collaboration because it sets the foundation for how individuals approach and engage in collaborative efforts. Here are some reasons why mindset is important in fostering successful collaboration:

- Openness to new ideas: A positive mindset encourages individuals to be open to new ideas, perspectives, and approaches. It promotes a willingness to listen, consider alternative viewpoints, and embrace diversity of thought, which leads to more innovative and effective solutions.

- Trust and psychological safety: A mindset that values trust and psychological safety creates an environment where team members feel comfortable taking risks, sharing their thoughts, and being vulnerable. Trust enables open communication, fosters mutual respect, and promotes cooperation, which are essential for effective collaboration.

- Growth and learning orientation: A growth mindset, characterised by a belief in continuous learning and improvement, is essential for collaboration. It encourages individuals to see challenges as opportunities for growth, embrace feedback, and adapt their approaches based on lessons learned. This mindset supports a culture of learning and agility, driving the team's ability to navigate complex problems and adapt to change.

- Accountability and ownership: A positive collaboration mindset emphasises personal accountability and ownership over collective goals. It instills a sense of responsibility for individual contributions and encourages proactive engagement. When team members take ownership of their roles and commitments, it fosters a culture of reliability, commitment, and shared responsibility.

- Resilience and adaptability: Collaboration often involves navigating through uncertainties and overcoming obstacles. A resilient and adaptable mindset helps team members stay focused, remain optimistic, and bounce back from setbacks. It enables individuals to adapt to changing circumstances, find creative solutions, and persevere towards shared goals.

Overall, mindset plays a pivotal role in creating a collaborative culture where individuals bring their best selves, foster positive relationships, and work together synergistically. It influences how team members communicate, problem-solve, and embrace challenges, ultimately shaping the success of collaborative endeavours.

I'm still wondering about dot point number 4, but overall, that's a pretty reasonable set of responses. Are you seeing these mindsets in your collaboration?

Exhausting Lessons in Communicating Across Barriers

As my wife will attest, I’m not a French speaker, but I do have a (very) basic vocabulary. This means that communicating when in France can be quite challenging, sometimes embarrassing, often hilarious. It struck me that my struggles to communicate in a foreign language are a little like the struggle to communicate with those who think differently to us in everyday life.

For example, I have a client in the stakeholder engagement team of a large utility. Their communication struggle tends to be with the internal infrastructure team who design and build the pipes, who come from a different background and see things through a different lens. Sometimes the teams feel like they are speaking different languages.

So what can a month in France teach me about that challenge? Well, despite my limited French I did manage to communicate using:

- Multiple channels, sometimes writing things down, even using facial expression and hand gestures to get my meaning across.

- I listened as loudly as I spoke. I concentrated very hard on what was being said to me and invested a lot of energy in clarifying meaning.

- Most importantly perhaps, I was highly motivated to communicate, as only being stranded on a rail platform in a foreign land can motivate a person. I wanted to understand and to be understood. I cared deeply about what was being said to me.

For my client this means trying diverse channels to deliver and receive messages to and from the engineers. It means really listening. Asking rather than telling. Being curious and wanting to know how ‘they’ see it.

Communicating in a foreign language is an enjoyable challenge, but it can be completely exhausting, which probably indicates how much I was investing in trying to communicate. I know that working with collaborators can be exhausting too, but perhaps that’s an indication of your commitment to working authentically with others. Working across barriers is tiring, but worth it.

The photo is of Estaing, one of the many beautiful villages we walked through on the Way of Saint James.

Whose Story Is It Anyway?

Over the years I’ve had a number of experiences that left a lasting impression on me, supercharging my belief in the value of doing ‘with’, not doing ‘to’. One such experience taught me that it really matters whose story is being told and who is telling it.

In this instance I was contacted by a local Council, asking me to facilitate a couple of public meetings to discuss Council’s proposed rate rise. The two meetings had already been scheduled and advertised. They were expecting a pretty negative reaction from ratepayers and were looking for someone to “manage the room”.

It was a pretty constrained and uninspiring brief, but in the few days prior to the first meeting I hatched a plan that, I hoped, might make the process more meaningful and useful to all.

The first public meeting arrived. I did my best to ensure Council made its case clearly and that ratepayers were heard. Council told their story of budget pressures and the need to repair things such as roads and bridges. After everyone had been heard I asked everyone to indicate their level of support for the rate rise, by placing a sticky note on a ‘spectrum’ from very low to very high. As expected, people on the whole didn’t want to pay higher rates. No surprises there.

Then before closing the meeting I called for some volunteers for a working group that would meet the following week with Council to dig deeper into the rates issue. We left the meeting with a dozen or so volunteers, many of whom were quite actively opposed to rate rises.

On the appointed day the group convened at Council and began a day of sharing, listening, questioning and learning. The day included a bus tour around the city to see first-hand the problems with existing infrastructure. The netball courts were unsafe. Rusty guardrails on the mountain road were no longer fit for purpose. The century-old wooden bridges were desperately in need of replacement. Stormwater drains needed work.

Working group members came back from that trip saying things like “I didn’t realise how bad the mountain road is” or “I had no idea it was so expensive to replace a drainage culvert”. At the same timer, Council staff heard stories about hardships among the community and the surprising expenses that small businesses faced.

The next evening we all went back for the second public meeting. This was another large event, open to all community members. This time, members of the working group were invited to share their experience and what they had learned. While much of the detail was the same as Council had already presented, these community members were telling their story. They spoke about their roads and bridges, and their kids who need safe sporting fields.

Was it received differently to Council’s story? Definitely. The final act of the process was to once again ask everyone at the meeting to indicate their level of support for the proposed rate rise on the same spectrum of support. And wouldn’t you know it? This time around, the majority was in favour.

When stakeholders get their fingerprints on a process, when they are extended the respect required to learn together, they are able to write their own story about the dilemma, rather than accept someone else’s. And this story carries a different power.

Whether you are the CEO of a Council, a Health Care organisation providing services to clients, or a manager with a team to work with, inviting your stakeholders to write their own version of the story can be an essential component of success.

Oscar Winners, Net Zero and the Skills Gap

Everything, everywhere, all at once is a great title for an Oscar-winning movie but according to one commentator it’s also the essential approach for progress towards a low carbon future.

I recently attended a thought-provoking panel session hosted by the Institute for Sustainable Futures (my alma mater as it happens), where global specialists on transition planning and implementation talked about the road ahead. It was more than a throwaway line from a panellist that everything, everywhere, all at once is what we need to be doing. Reaching net zero is hard and requires all hands to the pumps.

We heard that what is required is a “global collaborative effort to scale up” the transition across all sectors and all countries. That got my attention, along with the ensuing discussion about the economy-wide shortage of skills necessary for helping companies transition to low carbon operations.

What are the skills of doing everything, everywhere, all at once to meet our Paris commitments? Obviously there are a lot of technical skills required, such as scenario planners, financiers, electricians and a thousand others. Yet I believe there is a less obvious capability that will be needed and that is the suite of skills required to work across business-as-usual boundaries to make the systemic changes needed. These include:

Systems thinking as we grapple with whole supply chains and circular economies to find smarter ways to do more with less.

Experimental mindsets we will need in order to try things that just might work (and just might not), and to learn as we go.

Relationship building, essential to making the connections across networks of stakeholders, even where we are in competition for resources, market share, scarce dollars and scarcer people.

Customer, community and stakeholder engagement required as we bring the whole system into the room (figuratively and even literally) to co-create new ways of doing business.

To do everything, everywhere, all at once we will need an awful lot of collaborators, which raises some questions: Where are companies going to find people with these skills, and where are people going to learn those skills? Where are you going to look?

I'm making my own small contribution to closing the skills gap in April, with a short workshop on the core collaborative skill of co-defining the dilemma. Check it out and book .