Extending our thinking to be wiser together

“How are we going to implement this so that it works?” is a question that is often asked. All too often the default response is along the lines of “let’s do it the way we have always done it, but ‘more’, or ‘better’, or ‘with better enforcement’”. In other words, business as usual with the same results we’ve always seen.

If we are truly seeking to be wiser together when planning to implement a solution it pays to think creatively about how to do that, yet I know from my own experience that creativity doesn’t always come naturally. Sometimes things get in the way, such as:

- Organisational norms about what is acceptable or not,

- Unspoken assumptions about what is or isn’t possible or workable,

- Group think where we rapidly line up behind an idea,

- Unwillingness to say something out of the box lest it seem silly,

So far, so human. Yet, creativity and generative thinking are very human too, and with the right encouragement any team can be more creative.

Some teams can find a simple tool helpful, even if simply as a reminder to avoid the trap of BAU thinking. Our tool is appropriate for groups large or small and is designed to do just that. On its own it won’t save your project or the world, but as an action you can take in five minutes, it can help any group be wiser together.

and extend your thinking.

How to look at your project from another perspective

When seeking to be wiser together we are often called to walk in each other’s shoes, to look at the world from a different perspective. In short, to try to get inside another person’s head. Of course this is easier said than done, requiring effort, some discipline, and perhaps a simple structure to help.

Among our simple toolkit for collaborators is one we call . Like many of our tools it’s designed for use in any meeting or workshop, large or small. It is consciously simple and ‘low tech’ meaning anyone can use it any time. I find that clients use this tool as a gentle prod to walk in each other’s shoes rather than focus always on our own view.

Simple? Yes. Subtle? Probably. Useful? Like anything that helps us be more thoughtful, absolutely. and be wiser together.

Why taking the risky action is the path to reducing risks

Are you circling the wagons or leaning in to manage angry stakeholders?

I once had a client at a council where the General Manager had taken a battering over the years from a small number of vocal and angry community groups. By the time I was involved, the GM had effectively pulled up the drawbridge and stopped talking to his stakeholders.

This response to community anger is very understandable and a natural self-defence mechanism. Other ways we respond include to:

- Get angry that they are outraged at us. “How dare they! Can’t they see I’m doing the right thing? Of course I can be trusted and it’s offensive of them to say otherwise!”

- Go into defensive project management mode: Plan every move out before doing anything; Line up your ducks in an attempt to minimise the chance of pushback; For every move, seek permission from those up the line; Manage out any opportunity for untoward anger; Get stuck in analysis paralysis.

Of course the irony is that these actions are likely to exacerbate the very stakeholder anger you are trying to avoid. By managing to reduce outrage, we often increase the outrage.

Vulnerability is the secret to success

What to do instead?

Lots of things, many of which boil down to being vulnerable in the face of potential bad experiences. For example:

- Do more engagement, not less.

- Stop talking and start listening.

- Be curious without defending (“Is that right? Tell me more about why you feel that way….”)

- Talk. Remember that conversations build relationships, which make the transactions possible.

- Embrace uncertainty and do stuff. Less planning to manage out risk and more engagement, even when unsure about outcomes.

- Ask for their help.

- Extend trust to them, so that they might return the favour.

Back at this council with the besieged GM, I encouraged my client to go and talk to some of these people. To his credit he did just that and came back with a new spring in his step. It turns out that he and the GM’s number one ‘public nemesis’ grew up in the same suburb in the same city, and my client’s father coached the other guy at football. Connections were made. Barriers began to crumble. Frosty relationships began to thaw.

Circling the wagons is a natural response to scary situations and ‘leaning in’ to those situations feels very uncomfortable. But if you want to reduce the anger out there, leaning in to that vulnerability is the lower risk move. Can you risk doing anything else!

Are you managing risks or managing outrage?

By treating people as human we stand a chance of reducing their level of outrage, which is likely to reduce their sense of the risk.

I have recently had cause to delve back into the world of risk communication, where I was reminded of a couple of fundamental pieces of work that continue to feel relevant, even as the world seems to be filling up with outraged people.

The Factors That Contribute to a Perception of Risk

The first idea is that there is only a low correlation between the actual level of physical risk in a situation and the amount of concern it generates. Dr Peter Sandman and Dr Vince Covello have done a lot of work in this area over the years. They offer a list of factors that contribute to our perception of risk, including things like perception of fairness, novelty or knowability, control or lack of control, emotional impact, visible v invisible etc.

A key point for me is that as the proponent of a project or a change it is easy for me to 'know' the risk is low. But this bears no relationship to how risky it feels to others. If I feel like an innocent bystander subject to something I don’t want, it is hard for me to see this thing as anything other than risky, with lots of negative consequences. At which point I create the Facebook page.

Regardless of the actual risks posed, if a proposal ticks some of these boxes the project feels risky, which amounts to the same thing as far as stakeholder outrage goes. Which of the factors might your projects be tapping into?

This idea is neatly expressed in Dr Peter Sandman's famous equation: Perception of risk = hazard x outrage.

In other words my sense of the danger something presents is driven by how upset I am about it, rather than the other way around. While it always seems clear to me that my outrage reflects a rational assessment of the actual risks involved, Sandman shows us that the extent to which I think something is risky is largely driven by my level of emotional engagement. If I'm upset I think it's dangerous. If I'm not upset, I think it's safe.

Managing Risk Perception

These ideas from the risk comms world give us a strong clue about how to respond to an outraged community and it isn’t to present all the facts about why the project isn’t dangerous. Instead we must treat the outrage, rather than downplay the risk. This means listening, admitting negative impacts where there will be negative impacts, walking in their shoes and seeking to understand their perspective. Being vulnerable. Even apologising if that’s relevant.

By treating people as human we stand a chance of reducing their level of outrage, which is likely to reduce their sense of the risk.

Sound risky? Perhaps that’s our emotional response talking.

Vote 'Yes' to Listening and Curiosity

Vote 1 Polarisation

In Australia we are deep in the public ‘debate’ about the upcoming referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution. In the national media at least it tends to be less a debate and more a noisy process of defending one’s own opinions and deriding the others’.

The unseemly nature of the public discourse is perhaps inevitable given that we are looking at raw politics at play. But even without the political nature of the discussion a referendum is always polarising because it forces a binary choice. Yes or no. Support or don’t support. I am right, which means you must be wrong.

The dynamic that is forcing Australians into one of two camps – pro or con - comes at a cost to our national harmony. It’s also a great example of what to avoid when working with diverse stakeholders on complex issues, because binary debates are not only overly simplistic, they always force people further apart.

When I work to convince you of why I am right, while at the same time refuting your attempts to do the same, we can’t help but become further entrenched in our own positions. The distance between us can only grow, and we each become even more ‘wrong’ in the eyes of the other.

How to get unstuck

What can we do about it? When in this situation we need to reverse the polarising nature of the discussion, and find ways to talk that bring us closer together rather than drive us apart. Ultimately we want them to be curious about our ideas and perspectives, but this can be challenging because in order to do this we probably first need to be curious about and interested in their ideas and perspectives. That is, we need to:

- Stop talking and start listening.

- Be authentically curious about what they are saying and why.

- Help them articulate their position more clearly.

- Be genuinely open-minded.

Then perhaps they will start to explore our opinion.

When collaborating, don’t set up situations that become referendums on the question at hand. Rather, set up conversations full of exploration and learning. That’s how we make progress together on complex issues. I vote yes to that.

Down with Difficult Debates

“We need to have a difficult conversation with them”.

So said my client the other day when discussing their relationship with one of their key external stakeholders. And as they said it I could almost feel the tension in the air as they pondered that conversation. It felt difficult. It felt unpleasant. It felt dangerous.

Since the meeting I’ve been wondering why conversations that go a little deeper, that share a little more honestly, are seen to be ‘difficult’. I’d like my clients to see these situations as opportunities for learning, but it seems that we are all so entrenched in the model of debate and argument, winning and losing, wrong and right, that we can only see these discussions as adversarial.

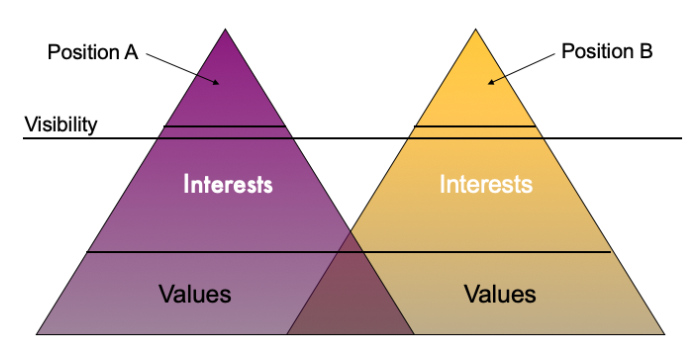

I often turn to our simple ‘Values Triangles’ framework to help make this dynamic visible for clients. It depicts two people, person A and person B, each with a strongly held ‘position’ or idea. We can see that between the two positions there is a space - the distance between us. And our adversarial thinking tells us that, when confronted with an opposing idea, our task is to argue our case and convince them that our position is the right one. The space between us grows. We become more entrenched and polarised in our views.

The framework also shows us that our positions are supported by interests, the reasons we think this is best, which in turn are supported by our values, our fundamental beliefs and things we hold to be important. It also illustrates that different positions can be supported by similar interests and values, and that we are likely to have more in common than we first think.

When my client is imagining a difficult conversation, I suspect they are imagining being stuck at the top of the triangles, having an argument about right and wrong. Difficult? Yes. Inevitable? Definitely no.

With a different mental model, one based around learning, curiosity, exploration and relationship building, we can have these conversations differently. We can explore each other’s interests and values. We can together create alternative positions.

With some simple skills and processes we can get out of our adversarial thinking and start learning together about what makes each of us tick. That’s an interesting conversation rather than a difficult one.

Failing to Reach the Summit of Collaboration

Remember Kevin Rudd’s Australia 2020 summit, billed at the time as a people’s forum to help “shape a long-term strategy for the nation’s future”. It was 2008. Rudd was a new and exciting Prime Minister who appeared determined to shake things up. The Summit looked like clear evidence that this government would do things differently, that here was a government that listened, led by a PM who wanted to bring us all on the journey.

The Summit was a very high-profile event, with 1000 delegates selected from across Australian society. Actors and other famous types were hand-picked to chair 10 working groups, each of 100 people. It was a big deal, an enormous event and a huge logistical undertaking, a massive investment in doing government differently. It looked like this government was actually trying to collaborate with us, the people. It was exciting.

Over two days Australia’s ‘best and brightest’ rolled their sleeves up and got stuck into some big and difficult issues. There was enough flip chart paper and sticky notes to sink a ship. At the end of the summit there were speeches and everyone went home exhausted, having done their best to nut out some hard problems.

A final report from the summit was handed down. 135 of the 138 recommendations were rejected.

And this is the difference between doing collaboration and being collaborative. To do collaboration was to get 1000 people in the room and ask them to come up with recommendations. Easy. But being collaborative, thinking like a collaborator, the PM would have recognised that:

- Authentically tackling complex problems requires investment in relationships, which in turn requires time and space for conversation.

- Learning is at the core of useful collaboration, and with it, the disagreement, challenge, exploration, joint fact finding and coming together that demonstrate we have learned from and about each other.

- Letting go of control and releasing power are essential to authentic collaboration. Micro-management of issues and scopes and information and messaging are anathema.

- Making decisions about the merit of recommendations is a key part of any collaboration. Do this with not to stakeholders.

- Genuine diversity of opinion is essential. Handpicking the ‘best and brightest’ is to impose my views on the event.

I believe the PM and his government were genuinely trying to do something different. But, as is often the case, they invested hugely in the doing without making the same effort in the being. And if there is one thing I have learned over the years, it is that being collaborative trumps doing it every time. When we think like collaborators we stand a good chance of authentically collaborating. The reverse is much less true.

So are you both doing collaboration and being collaborative?

Do Be Do Be Do Collaboration

To do is to be (Kant)

To be is to do (Neitsche)

Do be do be do (Sinatra)

So goes the undergraduate joke. But whatever these three famous philosophers may or may not have said, the joke reveals something important about collaboration. To be a collaborator requires us to do collaboration. And to do collaboration we must be collaborative.

Or to put it another way, authentic collaboration requires us to both think and act like a collaborator.

So far so obvious. And yet I see many organisations professing to do collaboration without having recognised the requirement to be different. And so they:

- Get their stakeholders in the room but retain control over key aspects of the conversation, such as the scope, the problem to be solved, who is invited, what data are relevant, who’s voice is heard, and so on.

- Ask for feedback in the name of collaboration, when they are more accurately consulting.

- Reserve the right to ignore or downplay collective decisions.

- Send the (often mostly female) customer engagement team out to ‘collaborate’, while retaining decision-making powers within the (often mostly male) 'core Divisions' of the business.

Authentic collaboration requires a shift in mindset as much as it does a shift in practice. Or to paraphrase our three philosophers: Real collaboration with real people on real problems requires us to do and be and do and be and do collaboration.

So does your organisation strive to be collaborative in order to do collaboration?

Isn't it great that we disagree?

Why disagreement and divergent views are the essential raw material of collaboration, to be embraced, acknowledged, even celebrated.

Recently I was involved in a project to find a solution to a challenging policy question. While running a workshop with stakeholders I did what I often do and asked each of the 40 people in the room to write down on a sticky note what they think is the problem to be solved by this policy. As is always the case, within 10 minutes we had 40 quite different views of the problem (and some 'solutions') on the wall for all to see. We went to a lunch break and the client came up to me and said something like “that's the problem. Everyone has a different opinion and we can never agree on anything!”.

Back in the workshop after lunch it was clear that the client’s view was widely shared. We disagree! We will never get alignment! This collaboration thing is doomed!

I understand this view, but I believe that the much bigger problem is that we see these differences as the problem. Because I’ve learnt that the 40 different views in the room are the raw material from which a great outcome will be generated.

As usual, my message to collaborators at this point is “isn’t it great that we all see this differently”. And I genuinely believe this for a number of reasons:

- Different opinions decrease the likelihood of ‘group think’ while making something novel more likely to emerge.

- The more differently we see this situation the more likely it is that we are capturing the bulk of relevant issues and concerns and opportunities. If we see things in a narrow way we are probably missing some important stuff.

- The fact that we see the situation differently makes working together more important. In other words, it builds the argument for more collaboration, not less.

- Inviting the difference helps us all see that we have a place in the discussion, that our views and experiences are relevant, even essential as part of the full picture.

- Acknowledging differences and working with them is a great way to build trust among collaborators. Listening across differences helps to build relationships.

So, the next time your collaborators express differences of opinion and are seeing things differently, you can feel ok to step into that difference and draw on it to create something that none could have thought of alone.

ChatGPT's take on Collaboration

Chat GPT was asked to explain the value of authentic collaboration. Here is it's reply, in full and unedited:

Authentic collaboration refers to a process in which individuals or groups work together towards a common goal by sharing their ideas, knowledge, and skills. The value of authentic collaboration lies in its ability to generate innovative solutions and foster a sense of community among team members.

Here are some key benefits of authentic collaboration:

- Diverse perspectives: When people from different backgrounds and experiences collaborate, they bring different perspectives and ideas to the table. This can lead to more innovative solutions and creative problem-solving.

- Improved communication: Collaborating requires open and effective communication, which helps build trust and respect among team members. It can also reduce misunderstandings and conflicts, leading to a more productive and positive work environment.

- Increased efficiency: By sharing knowledge and skills, team members can accomplish tasks more efficiently and effectively. Collaborating can also help to streamline processes and eliminate redundant efforts.

- Personal and professional growth: Collaborating with others can provide opportunities for learning and development, as team members can learn from each other's strengths and weaknesses. It can also help individuals build new relationships and expand their networks.

Overall, authentic collaboration can lead to greater creativity, productivity, and job satisfaction. By working together towards a common goal, individuals and groups can achieve more than they could on their own.

What do you make of this summary? It seems hard to disagree with any of it, but at the same time, I know that there is much more to say in answer to this question. Meanwhile, are you living up to ChatGPT's expectations of your authentic collaboration?