Fingerprints on the bypass

I was thinking about our topic this month of Co-design, or "getting fingerprints on the process" and it reminded me of a story from a couple of years ago.

"A roading authority was planning the route for a major highway bypass around a small coastal town that had been a traffic bottleneck for some time. One of the loud voices was a vehement environmental advocate and local Councillor who was strongly opposed to any bypass due to the adverse environmental impact on the surrounding farmland and forests.

Recognising the potential controversy, the authority put a lot of effort into involving the local stakeholders in the decision making on the bypass options. While being opposed to any option, the activist did participate in the process.

At the end when the preferred option was agreed and actioned, the activist reflected on his involvement, and reported that while he still disagreed with the decision to proceed with the bypass, he could live with the decision because of the way he had been involved - and in fact that he was quite supportive because of the way he saw his "fingerprints" on the process. He noted that the process had been open and fair, and he felt he and his views had been considered and respected, a range of views had been explored, and he had been able to influence the process in some way".

Knowing a bit about the activist's previous strong positions, I remember being a bit surprised at the time by his reaction- to seemingly support something so strongly at odds with his position.

In hindsight I now recognise some of the characteristics of the process that likely contributed to such an outcome:

- an invitation to participate

- the authority sharing power a little, just in terms of how to do the assessment

- feeling listened to, involved and respected

- the authority sharing information openly helping to build trust

- people feeling ownership of the selection process, leading to an increased commitment to the outcome

- the authority asking for help and not just imposing either the process or solution

These are some of the elements of that we see as a critical step in getting from argument to agreement on tricky issues.

How often might you bypass the fingerprints?

There is co-design, and then there is co-design...

Co-design is a word on many lips these days, but there is co-design, and then there is co-design!

People often use co-design to mean a process that invites stakeholders in to jointly solve a particular problem. But there is a more nuanced and powerful way to think about it.

Fingerprints on the process

In our Power of Co framework Co-design is one part of a structured, holistic collaborative process. While the whole framework is about inviting stakeholders in to tackle complex problems together, co-design is specifically about ensuring that stakeholders have their fingerprints on the process. Successful collaboration requires that all collaborators have a say in how they will work together. They are not simply invited into a pre-defined collaborative process. They are invited in to help design it – every step of the way.

Having worked on some very complex collaborations we have learned the importance of getting fingerprints on process. When stakeholders share process decisions they:

- Become more invested in and supportive of the process, which really helps when things get tough and trust becomes critical;

- Are more likely to accept outcomes of the process because they had a share in designing it;

- Add their intelligence and creativity to ensure the process works best for everyone;

- Step up and share accountability for how this process is running;

- Feel like partners rather than pawns in someone else’s process fantasy (they are done ‘with’ not done ‘to’);

- Develop trust and a stronger working relationship.

Through authentic collaboration, the idea of co-design becomes second nature and an integral part of your daily work. Rather than sitting at your desk sweating over how to run the next meeting you will find yourself asking participants what they would like to do. Instead of trying to work out what information your stakeholders will find most useful, you will ask them. Rather than mapping out the Gantt chart for the project and doing it ‘to’ your stakeholders you will plan each step with your collaborators as you go.

So when you next hear someone saying they are running a “co-design process”, you might ask just how much involvement stakeholders have had in co-designing the process. If the answer is “not much, but they are involved in finding a solution” then perhaps a critical piece of collaboration has been overlooked.

Do your stakeholders have their fingerprints on your processes?

Listening and the Politics of Humiliation

Why do you listen to people? When I ask this question of clients and others I tend to get answers focussed on the content: "listening lets me learn something I don't know". There is no argument from me on that point. But why would you listen to others when you don't think you can learn anything from them? One obvious answer is that you are probably wrong about that, and you almost certainly will learn something. But here I'm interested in another answer that is important to all collaborators.

In a recent opinion piece, New York Times Columnist Thomas L. Friedman wrote about the "politics of humiliation" and suggested that humiliation is one of the strongest, most motivating emotions we can experience. He quotes Nelson Mandela as saying "there is nobody more dangerous than one who has been humiliated". Then Friedman goes on to make the point that the countervailing emotion is respect. "If you show people respect, if you affirm their dignity, it is amazing what they will let you say to them or ask of them".

And this brings me to the second answer to my earlier question. One of the reasons to really listen to someone, even when we don't expect to learn something from them, is to show them respect and affirm their dignity. As Friedman writes: "Sometimes it just takes listening to them, but deep listening - not just waiting for them to stop talking. Because listening is the ultimate sign of respect. What you say when you listen speaks more than any words."

Those who feel humiliated will never collaborate; Those who feel disrespected will never collaborate; Those who feel unheard or ignored will never collaborate unless and until they feel respected. And as Friedman says, one way to clearly demonstrate our respect for another is to listen to them deeply.

Friedman is writing in the context of US politics, but the message seems universal to me. In order to work effectively with others to tackle hard problems together we need to genuinely respect them, and demonstrate that respect in the way we act. Listening holds the key.

So now let me listen to you. What is your takeaway from Friedman's article?

The Agony of Silence

Thinking about this month's theme of listening I've been reflecting on why I find it so hard to be silent in a group environment- to pause and wait for others to speak. In my experience as a facilitator and coach, I feel this tension almost every time I work. That growing anxiety as I pause and wait for input or a response from someone else in the room or on the zoom call. But why do I feel this way?

- Is it that I feel inadequate if I'm not contributing or controlling the conversation?

- Is it that I worry my client won't be getting value if I'm not talking?

- Is it that I just have so much valuable stuff to say that I must get it out?

- Is it that I don't want to give others a chance to get their threepence worth in?

- Am I worried that they might say something contradictory?

- or even worse, they might say something more insightful or valuable than I could?

The palpable tension as the pause lengthens, and silence fills the space.

What are they thinking? Will someone step up? What happens if they don't, and will it seem like I've wasted their valuable time being quiet.

It's a ridiculous fear really, that a 30-second pause might result in a failure to meet a deadline, or get a job done, or meet the boss's needs, particularly as we have already used 10 times more than that on arguing who is right or wrong on some aspect of the issue.

And then relief! Someone steps in with an insight, a question, a comment, an idea. It cascades from there like a dam has broken and overwhelms those assumptions and anxieties.

So I have learnt that the pain of being silent is one of the keys to listening more effectively. But this insight doesn't make it any easier to keep my mouth shut for those seemingly interminable seconds!

A hop, skip and jump into collaboration

When facing any problem at work, our natural tendency as a leader is to seek a clear process to find solutions.

A step by step guide that gives us confidence we are on the right track, and can get the desired outcome. It would seem that part of the attraction is our need to know, and to be seen as a good problem solver (otherwise we might look a bit incompetent??)

Now it seems that in a lot of circumstances this works just great, but what about those wicked and complex problems where our standard problem solving fail and we need new thinking to tackle it together.

We've spent a fair bit of time trying to make sense of this dilemma- how to provide a step by step guide to solve complex issues when the nature of complexity dictates that a linear approach will fail!

Our insight is that we need to treat such situations more like a dance than a climb- taking a flexible approach allows for the emergence necessary when taking a more collaborative approach.

We can still generate a framework and set of tools in a logical sequence to provide guidance, but we are seeing growing evidence with clients that being able to "hop, skip and jump" is key to success. This might look like

- starting at the appropriate place in the logic given your situation- maybe step 3 or 7....

- moving back and forward through the logic as needs dictate

- missing some steps if needed

- starting anywhere, but going everywhere.

While you might need to understand the framework and know how to use any particular tool, a key success factor will also be to know what tool to use when- the hop, skip and jump approach.

If you want to know more about how to do this, talk to us about applying our Collaboration System.

How to move from open warfare to solution-finding

Getting agreement among people who have diverse and strongly-held opinions is challenging, there is no doubt. But sometimes we make it more challenging than it needs to be by focussing on opinions, rather than seeking to understand why we hold them.

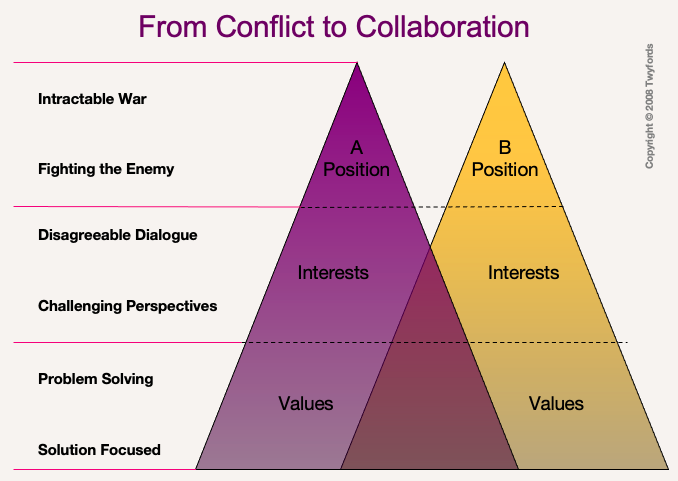

Here is a simple model to illustrate. We call it the values triangle.

The two triangles represent two people, each with a very different and strongly held opinion about an issue they must work on together. Let’s call that opinion their Position, as in “this is the position I’m taking on this issue”.

We can see that there is a lot of space between the two positions at the top; a gulf between how person A and person B see this situation. In this case the discussion often becomes a battle of wills, an argument between opposing sides, a 'war' where each side seeks to win while ensuring the other loses.

But let’s go deeper. We can see that the position each person holds is supported by their Interests, the things that they want. Person A holds position A because he feels it will deliver on his interests. Person B does the same with her position and interests. But too often neither person learns the interest of the other as they are too busy defending their own position and attacking the other.

And then let’s go deeper again. We can see that our interests are consistent with the fundamental Values we hold, our deep sense of the way the world is and should be. Often we struggle to articulate these values to ourselves, let alone share them with those we disagree with. Yet we can see that our values are often much more similar than we might imagine. We have much more in common than we expect.

And yet, because we are stuck trying to win the argument about our positions we can be deaf and blind to the values of the other. No wonder agreement can be so difficult!

Collaboration requires us to recognise that a person’s strongly-expressed opinion is not the sum total of who they are. They hold that position because it seems to them at least to support their interests, which will be consistent with their deep values. And their deep values are likely to be not too different to mine. If we can find ways to have conversations about the things that really matter to us about the current problem, we are much more likely to find common ground, to stop arguing and start listening. Best of all, we are much more likely to emerge from the discussion with a brand new idea that better matches the situation, and which we all own.

So the next time you have to wrangle people where there is a lot of disagreement about the way forward, you may want to encourage everyone to do less talking about their idea and more exploring of others’ positions, interests and values. If you would like to know more about how to do that talk to us about our collaborative processes, which incorporate a number of tools for shifting from argument to agreement.

The Dilemma- a chip off the old bloke

As I ponder on the past and emerging dilemmas in 2020 - like the recent bushfires, the current coronavirus crisis, and key challenges like indigenous disadvantage, deteriorating mental health and risks from climate change, I'm often a bit disappointed and frustrated by the simplistic and solution focused ways in which we tend to respond.

It seems like "I know the answer, you just need to listen to me and implement what I say, and all will be OK".

Given the complex nature of such challenges, stepping back from the answer and taking some time to explore the question first is being increasingly recognised as a more useful approach, particularly given the history of failures applying the business as usual "solution" approach.

So Einstein's quote from long ago would still seem very relevant ie

"If I had an hour to solve a problem, I would spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem, and 5 minutes thinking about the solutions".

However while thinking- and talking together - about getting on the same page is a crucial first step, the emerging dilemma can look a bit too big and complex, perhaps overwhelming, and it can be hard to know where and how to get started.

In our experience, finding a chunk of the problem to focus on can be really useful - something that feels feasible, relevant and achievable to start with.

A "right sizing" exercise can focus the efforts on to a piece of the problem, with greater confidence that it:

- is substantive, but doable

- warrants our time and resources

- motives us and other stakeholders

- potentially leads to a useful result

- really matters to those involved

So perhaps we should ask Einstein to sacrifice a bit of that hour to right size the dilemma?

One thing the populist response to COVID tells us about collaboration

The global COVID pandemic, as tragic and difficult as it is, offers many insights into how people and nations respond to wicked problems. An insight that stands out for me is the value of working to understand the problem faced before leaping to solutions. We call this co-defining the dilemma. When done poorly you get Brazil’s COVID response. When done even half well you get something like Australia’s.

So what is the COVID dilemma? A better question would be ‘what are the many dilemmas inherent in this situation? Let’s pick the central two dilemmas within the dilemma, which every country is obviously grappling with:

- How do we minimise the impact of the virus on our health?

- How do we minimise the impact of the virus on our economy?

In many ways these two dilemmas are poles apart – we kill the virus by closing down, which probably kills the economy. Yet we protect jobs by staying open, meaning party time for the virus.

It’s challenging, yet it seems that many jurisdictions haven’t come to grips with the dilemma here. Of course they have acknowledged the pieces but they don’t seem to have framed them as a dilemma to be addressed. Rather they slide into a simplistic ideological battle; On the one hand “we have to lock down to keep us safe”. On the other, “we have to stay open to protect the economy”.

In some countries this over-simplistic thinking has resulted in an over-simplistic ‘plan’ to keep things open as much as possible, protecting jobs and the economy. Of course, this approach has implications reflected in a climbing death toll and in the end a likely massive economic hit as well.

What might they do differently? Lots, obviously. But my contribution would be to get agreement on the dilemma in order to open up the domain of possible responses. Put very simply this could be something like: how do we best respond to this virus and its impacts in ways that keep us safe and healthy while strengthening the foundations of a resilient and productive economy?

This type of framing of the dilemma isn’t an invitation to go to war over solutions. It isn’t an either-or-problem. It is a this-and dilemma that stakeholders need to work on creatively together. Importantly, it contains some insight into what success looks like in the long term – safe, healthy and resilient. These are things we can all work towards, regardless of our ideology.

Understanding the dilemmas instead of arguing over competing ‘solutions’ to poorly understood problems is such a simple yet powerful idea. And what is true of a national pandemic response is also true of a small organisational, issue. Time taken to co-define is always time well spent. What is your dilemma and to what extent do all stakeholders understand it and agree?

To learn how you can co-define your dilemma, take a look at our Power of Co System.

What makes you do different?

While reading Stuart and Viv's great new blogs to get some inspiration for this month's topic, I noticed the tag line at the bottom of our blog page- about our programs "building your collaborative muscle"

Then I thought ...aahh...I'm actually in the middle of something just like that- my continuing recovery from my surgery for my ruptured quad tendon, particularly re-building the quad muscles that had atrophied from lack of use.

So why is this a time to try something different?

I've realised that I just have to, because:

- I can't do what I normally used to do

- there's a high risk to my future (mobility) if I push what I normally do

- when I try to fix something it doesn't seem to work the same as before

- I'm willing, but others aren't (in this case my leg!)

- I revert back to business as usual pretty quickly

So what am I now doing that I may have avoided before, not even considered, or been embarrassed to try?

- slowing down hugely (easier when your body forces that on you)

- asking for help (eg requesting a wheelchair at the airport)

- following a really rigorous 12 month rehabilitation plan (that actually changes weekly depending on progress)

- but also accepting that I might just have to let things emerge, as I can't predict or plan everything (eg improving knee flexibility past 90 degrees)

- constantly experimenting with new ways to get things done (climbing stairs, crossing slopes, working permanently from home)

- Letting go of some things (being OK to not control everything- because the damn leg just won't respond)

- sharing the load at home and work (could be just an excuse to avoid cleaning the shower!)

And I'm actually seeing that trying something different isn't just really useful when I am faced with a complex and uncertain situation that challenges almost everything I do, but it's actually the only way to get the type of progress I need to reach my vision- skiing black runs again within 12 months- Covid permitting!

So I'm wondering what's your try-different story? Hopefully not as debilitating as mine!

Is it time to do something different?

This is a very appropriate title for my blog this month as I, personally, am about to do something very different that is simultaneously exciting, scary, sad and makes me feel vulnerable. Yes, I’m going to step back from 59 years of (almost) regular work and 32 years since I founded Twyfords in 1988. I’m going to step into the unknown world of “retirement’.

I’m doing it because it seems like a sensible way of approaching the rest of my life. I don’t know what it will look like, I don’t know what it will feel like. I have already received advice that ‘transition to retirement is not always as easy as many people expect’ and that I ‘should have a retirement plan’.

What I have learned over this last decade of exploring collaboration is that, when facing an uncertain future, full of ambiguity, which is likely to include complex decisions about many things, and likely to be dependent on the input of many other people, careful planning isn’t necessarily going to help.

So, my plan is not a detailed plan but more of a heuristic to live by as I let the future emerge. My notes to myself are: keep my body active through regular local and long distance walking; keep my mind active by learning new things and reading more widely; and finally continue to attempt things that challenge me.

While musing about this future, after 32 years I’m unable to switch off the habit of considering Twyfords future, in parallel to my own.

I am excited for the possibilities for the company, and sad that I won’t be such an active participant as in the past. We’ve been working hard during the uncertainties of the Covid-19 environment, the anxieties of the Black Lives Matter movement all embedded in the planet’s vulnerability to climate change. It’s pretty obvious to us just how important collaboration is going to be at every scale.

Twyfords theme this month is ‘Is it time to do something different?’

By this we mean, isn’t it time to think and act differently and improve our people’s capability to work really effectively with others on tricky, messy issues where complexity and uncertainty abound?

We asked our networks and their networks to respond to a quick 60 second survey. We are delighted at the number of responses we’ve had. We are finding evidence that the challenges facing project managers who want to lead their teams into more productive ways of working are the challenges our work is focused on solving i.e.

- They are looking for ways to ‘nudge’ their people to work differently and more constructively together.

- They seek confidence in leading a diverse team as it tackles difficult projects.

- They want to ‘add’ collaboration to their project management skillset for the future and

- They want to be able to ‘manage up’ and influence their managers and executives to support this new way of working.

I am confident that my colleagues at Twyfords, starting immediately, have solutions for project managers within organisations that struggle with:

- impermeable silos,

- a risk averse culture,

- a technical focus ... and most specifically

- a lack of support for ‘doing different’.

I wish them, as well as old and new clients, an exciting, but sometimes a little scary, way of ‘doing different’ where both authenticity and vulnerability will lead them into new ways and new success.

I’m also confident those ways of thinking and working will help me as I step into my new world as well!