Are you managing risks or managing outrage?

By treating people as human we stand a chance of reducing their level of outrage, which is likely to reduce their sense of the risk.

I have recently had cause to delve back into the world of risk communication, where I was reminded of a couple of fundamental pieces of work that continue to feel relevant, even as the world seems to be filling up with outraged people.

The Factors That Contribute to a Perception of Risk

The first idea is that there is only a low correlation between the actual level of physical risk in a situation and the amount of concern it generates. Dr Peter Sandman and Dr Vince Covello have done a lot of work in this area over the years. They offer a list of factors that contribute to our perception of risk, including things like perception of fairness, novelty or knowability, control or lack of control, emotional impact, visible v invisible etc.

A key point for me is that as the proponent of a project or a change it is easy for me to 'know' the risk is low. But this bears no relationship to how risky it feels to others. If I feel like an innocent bystander subject to something I don’t want, it is hard for me to see this thing as anything other than risky, with lots of negative consequences. At which point I create the Facebook page.

Regardless of the actual risks posed, if a proposal ticks some of these boxes the project feels risky, which amounts to the same thing as far as stakeholder outrage goes. Which of the factors might your projects be tapping into?

This idea is neatly expressed in Dr Peter Sandman's famous equation: Perception of risk = hazard x outrage.

In other words my sense of the danger something presents is driven by how upset I am about it, rather than the other way around. While it always seems clear to me that my outrage reflects a rational assessment of the actual risks involved, Sandman shows us that the extent to which I think something is risky is largely driven by my level of emotional engagement. If I'm upset I think it's dangerous. If I'm not upset, I think it's safe.

Managing Risk Perception

These ideas from the risk comms world give us a strong clue about how to respond to an outraged community and it isn’t to present all the facts about why the project isn’t dangerous. Instead we must treat the outrage, rather than downplay the risk. This means listening, admitting negative impacts where there will be negative impacts, walking in their shoes and seeking to understand their perspective. Being vulnerable. Even apologising if that’s relevant.

By treating people as human we stand a chance of reducing their level of outrage, which is likely to reduce their sense of the risk.

Sound risky? Perhaps that’s our emotional response talking.

Three Ways to Achieve More Learning in Meetings

One of the things that clients most appreciate is our suite of tools for collaborators. In creating this toolkit we sought to ‘bottle’ as much as possible of our collective experience, philosophy and style, so that clients could bring that to their own work without requiring us to be in the room.

On the theme of making difficult conversations safer and get more learning together, here are three tools designed to help people talk and learn across different views, experiences and opinions. Each comes from the section of our suite concerned with encouraging exploration of issues prior to making decisions. Use them in any meeting or workshop. Note that each tool is designed to help people release their strongly-help ‘positions’ – if only briefly – and to go deeper. For more about this see .

This process asks people to have a go at articulating the reasons and rationale behind the opinion that they don’t support. In other words it encourages me to put aside my ‘position’ and walk in the shoes of another, if only briefly. Use it when you want people to really consider other perspectives before making choices.

This process pairs people up and encourages each person to use generative questions to explore the thinking behind the issue at hand. What you are really doing here is making it a little more likely that different perspectives will be drawn out, heard and more deeply explored, prior to making decisions.

This process is a variation on Practice Curiosity, with a key difference being that each person in a pair is invited to first be curious about and then to advocate for the position that they don’t hold or the view they disagree with. Once again it encourages people to listen as loudly as they speak – an important part of any effective communication.

If you are facing conversations that you fear may be ‘difficult’ and if you are looking for some ways to make them both safer and more useful, why not give these processes a try. Let me know how it goes, and feel free to be in touch if you’d like me to talk you through it prior to your meeting.

Vote 'Yes' to Listening and Curiosity

Vote 1 Polarisation

In Australia we are deep in the public ‘debate’ about the upcoming referendum on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution. In the national media at least it tends to be less a debate and more a noisy process of defending one’s own opinions and deriding the others’.

The unseemly nature of the public discourse is perhaps inevitable given that we are looking at raw politics at play. But even without the political nature of the discussion a referendum is always polarising because it forces a binary choice. Yes or no. Support or don’t support. I am right, which means you must be wrong.

The dynamic that is forcing Australians into one of two camps – pro or con - comes at a cost to our national harmony. It’s also a great example of what to avoid when working with diverse stakeholders on complex issues, because binary debates are not only overly simplistic, they always force people further apart.

When I work to convince you of why I am right, while at the same time refuting your attempts to do the same, we can’t help but become further entrenched in our own positions. The distance between us can only grow, and we each become even more ‘wrong’ in the eyes of the other.

How to get unstuck

What can we do about it? When in this situation we need to reverse the polarising nature of the discussion, and find ways to talk that bring us closer together rather than drive us apart. Ultimately we want them to be curious about our ideas and perspectives, but this can be challenging because in order to do this we probably first need to be curious about and interested in their ideas and perspectives. That is, we need to:

- Stop talking and start listening.

- Be authentically curious about what they are saying and why.

- Help them articulate their position more clearly.

- Be genuinely open-minded.

Then perhaps they will start to explore our opinion.

When collaborating, don’t set up situations that become referendums on the question at hand. Rather, set up conversations full of exploration and learning. That’s how we make progress together on complex issues. I vote yes to that.

Down with Difficult Debates

“We need to have a difficult conversation with them”.

So said my client the other day when discussing their relationship with one of their key external stakeholders. And as they said it I could almost feel the tension in the air as they pondered that conversation. It felt difficult. It felt unpleasant. It felt dangerous.

Since the meeting I’ve been wondering why conversations that go a little deeper, that share a little more honestly, are seen to be ‘difficult’. I’d like my clients to see these situations as opportunities for learning, but it seems that we are all so entrenched in the model of debate and argument, winning and losing, wrong and right, that we can only see these discussions as adversarial.

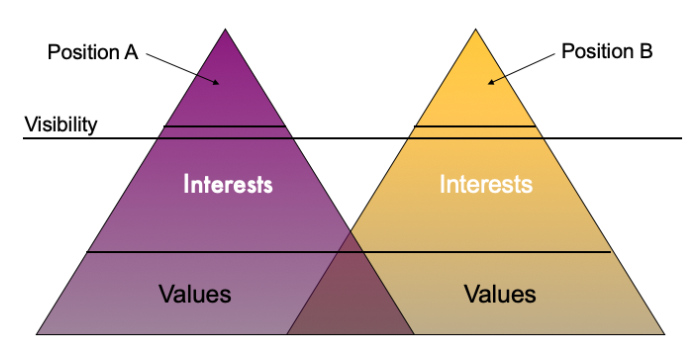

I often turn to our simple ‘Values Triangles’ framework to help make this dynamic visible for clients. It depicts two people, person A and person B, each with a strongly held ‘position’ or idea. We can see that between the two positions there is a space - the distance between us. And our adversarial thinking tells us that, when confronted with an opposing idea, our task is to argue our case and convince them that our position is the right one. The space between us grows. We become more entrenched and polarised in our views.

The framework also shows us that our positions are supported by interests, the reasons we think this is best, which in turn are supported by our values, our fundamental beliefs and things we hold to be important. It also illustrates that different positions can be supported by similar interests and values, and that we are likely to have more in common than we first think.

When my client is imagining a difficult conversation, I suspect they are imagining being stuck at the top of the triangles, having an argument about right and wrong. Difficult? Yes. Inevitable? Definitely no.

With a different mental model, one based around learning, curiosity, exploration and relationship building, we can have these conversations differently. We can explore each other’s interests and values. We can together create alternative positions.

With some simple skills and processes we can get out of our adversarial thinking and start learning together about what makes each of us tick. That’s an interesting conversation rather than a difficult one.

Do Be Do Be Do Collaboration

To do is to be (Kant)

To be is to do (Neitsche)

Do be do be do (Sinatra)

So goes the undergraduate joke. But whatever these three famous philosophers may or may not have said, the joke reveals something important about collaboration. To be a collaborator requires us to do collaboration. And to do collaboration we must be collaborative.

Or to put it another way, authentic collaboration requires us to both think and act like a collaborator.

So far so obvious. And yet I see many organisations professing to do collaboration without having recognised the requirement to be different. And so they:

- Get their stakeholders in the room but retain control over key aspects of the conversation, such as the scope, the problem to be solved, who is invited, what data are relevant, who’s voice is heard, and so on.

- Ask for feedback in the name of collaboration, when they are more accurately consulting.

- Reserve the right to ignore or downplay collective decisions.

- Send the (often mostly female) customer engagement team out to ‘collaborate’, while retaining decision-making powers within the (often mostly male) 'core Divisions' of the business.

Authentic collaboration requires a shift in mindset as much as it does a shift in practice. Or to paraphrase our three philosophers: Real collaboration with real people on real problems requires us to do and be and do and be and do collaboration.

So does your organisation strive to be collaborative in order to do collaboration?

Isn't it great that we disagree?

Why disagreement and divergent views are the essential raw material of collaboration, to be embraced, acknowledged, even celebrated.

Recently I was involved in a project to find a solution to a challenging policy question. While running a workshop with stakeholders I did what I often do and asked each of the 40 people in the room to write down on a sticky note what they think is the problem to be solved by this policy. As is always the case, within 10 minutes we had 40 quite different views of the problem (and some 'solutions') on the wall for all to see. We went to a lunch break and the client came up to me and said something like “that's the problem. Everyone has a different opinion and we can never agree on anything!”.

Back in the workshop after lunch it was clear that the client’s view was widely shared. We disagree! We will never get alignment! This collaboration thing is doomed!

I understand this view, but I believe that the much bigger problem is that we see these differences as the problem. Because I’ve learnt that the 40 different views in the room are the raw material from which a great outcome will be generated.

As usual, my message to collaborators at this point is “isn’t it great that we all see this differently”. And I genuinely believe this for a number of reasons:

- Different opinions decrease the likelihood of ‘group think’ while making something novel more likely to emerge.

- The more differently we see this situation the more likely it is that we are capturing the bulk of relevant issues and concerns and opportunities. If we see things in a narrow way we are probably missing some important stuff.

- The fact that we see the situation differently makes working together more important. In other words, it builds the argument for more collaboration, not less.

- Inviting the difference helps us all see that we have a place in the discussion, that our views and experiences are relevant, even essential as part of the full picture.

- Acknowledging differences and working with them is a great way to build trust among collaborators. Listening across differences helps to build relationships.

So, the next time your collaborators express differences of opinion and are seeing things differently, you can feel ok to step into that difference and draw on it to create something that none could have thought of alone.

Diving in to a collaboration mystery

“It has been great just to spend time on this together. We so rarely come together like this.”

“I was pretty sceptical walking in but having been a part of this workshop over the past few days I feel quite positive. It has been a very useful.”

When I hear comments like these from participants in workshops I’ve been facilitating I find it gratifying of course. But I also find it a little frustrating. My automatic thought is “if it’s so useful, why don’t you do this more often?”

I can’t remember when participants last found that the time spent working together in the room wasn’t useful. So it has always puzzled me that workshops with diverse people from across the organisational system aren’t a regular thing. I know I am biased but they feel so self-evidently productive from where I sit.

The quotes above are both from senior leaders in state government at the completion of a set of workshops I recently ran. Over three days this group tackled the task of creating a high-level plan for a new bit of complex policy. It is challenging work involving some quite challenging concepts and practices, yet after three days they felt they had made excellent progress.

So why aren’t workshops among senior people more of a thing?

I put this question to the project team, who had so ably helped to design and facilitate the sessions (big shout out to them). Their blunt reply was that “most workshops are pretty crappy”.

At which point it all made sense. Why would busy leaders want to come together for those terrible ‘talkfests’ we keep seeing? In their shoes I would run a mile too. Yet the opportunity cost of not coming together regularly seems very high, when I consider how productive diverse groups can be. Not only do they foster new ideas but they build shared understanding and much greater ownership of and commitment to the outputs. Doesn’t every leader want that?

The message seems clear. Nobody wants to waste time in a talkfest, and poorly-managed meetings have given all workshopping a bad name. But a thoughtfully designed and facilitated ‘workfest’ is a different beast. While I understand the impulse to avoid poor meetings, a great workshop always adds value.

At least I now know why workshops aren’t more common; People are understandably scared of wasting their time. So my next question is how can organisations best avoid poor meetings and boring talkfests while finding ways to do productive work together?

Hmmm…that’s a good topic for a workshop…..

The image is of a game of Underwater Hockey, a great sport that was a big part of my life at one time. If you haven't played it, go and check it out where you live. Like all team sports it involves lots of collaboration, and successful teams are more than the sum of their parts. photo credit Caleb Ming for ESPN

The Diamond Ring of Decision-making

Complex problems require a different approach.

In my I wrote about Sam Kaner’s Diamond of Participatory Decision-Making, which has always helped me think about what authentic collaboration feels like. It can be hard work.

The diamond shows us that after some ‘groaning’ we get to a point where we can converge on an outcome or outcomes, which has always been very encouraging. Yet I also know that when confronting our more complex and intractable problems the reality is that we rarely get to ‘the answer’.

For example, improving water quality and management at a catchment level is one of those ‘forever’ problems that never really go away. Catchments and all that goes on within them are an ever-evolving suite of dilemmas, dynamics, pressures and responses. We can always improve what we do, but the problems are never ‘solved’.

So what does this mean for the diamond of participatory decision-making? As a map for visualising how we tackle complex problems, perhaps the diamond is actually a circle. Rather than getting to the end, we continuously cycle back, through periods when our thinking is diverging and periods when our thinking is converging.

I have tried to illustrate this idea here.

I see this journey as a cycle of learning. In a way we never leave Kaner’s ‘groan zone’. Rather we recognise that when dealing with hard problems we are always sitting with uncertainty, incomplete knowledge, unintended consequences, different worldviews and different ideas. While outcomes are always important, our overarching approach is not about finding ‘the answer’ but about constantly finding new questions to ask and new ways to test our understanding and our ideas. Dave Snowden of fame suggests we “probe, sense and respond” in the complex domain. That is, we test ideas. When we find things that seem to work, we do more, building on success while always watching for signs that this is no longer delivering.

One way to look at this cycle is to see that it is groaning all the way down! But let’s embrace the complexity and reframe our approach from groaning to growing, from solving to learning, from convergence on the answer, to convergence on ideas as we go.

Perhaps this is the diamond ring of participatory problem solving?

From Groaning to Growing With Your Collaborators

“It was hard today. It felt like we did more arguing than anything and I’m not sure we made any progress!”

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve heard comments like this from clients. I’ve made the same comments myself from time to time. You may have too, because, let’s face it, working with diverse groups on difficult problems can be hard. We seek agreement, decisions, progress, but can’t seem to avoid frustration and exasperation as we ‘wade through treacle’.

Groan!

And those times that make us groan feel like failure. “What am I doing wrong?”

But what if you and your collaborators saw the tough times as the most useful times? What if you reframe that experience as not groaning but growing?

Yeah, I had the same reaction. But then someone pointed me to the Diamond of Participatory Decision-Making from Sam Kaner. This little framework gave me a whole new way to think about the collaborative journey and the role, even the value, of what Kaner labelled the groan zone.

What Kaner showed me was that the groaning is necessary, not evidence of failure. The tough times are the mother of innovation, invention, inspiration. That is, when we are groaning, it tells us we are doing the difficult work of collaborating on hard things together. If it was easy we would have solved this ages ago. If we are disagreeing it shows that this is important to us. And if we are challenging each other, we stand a chance of learning something new and finding novel solutions together.

Our fight or flight instincts are strong, and we tend to shy away from conflict, or do anything to avoid going there. But a quick look through clearly shows us that the urge to avoid the groaning and get to the decision is itself the thing to be avoided. When working together we need to allow time and space for divergent thinking where new ideas and new questions emerge. We need to allow time and space for convergent thinking where we get to agreement and answers. And the journey from one to the other is through the groan zone.

Yes, collaboration on complex problems is hard work. But that groaning you hear is the sound of old ideas fading and new ideas emerging. It is the sound of exploration. It is the sound of growing. Enjoy it while it lasts.

Resetting your collaboration

In Stuart’s , he identified some signs that a reset might be necessary. Let’s look now at what a reset might look like….

Having decided that something needs to be done, the typical response is to focus on structural, process and content issues. For example, the way we are set up, and the way people are working, especially the behaviours we see and don’t like, redesigning meetings or agendas, getting a better facilitator, managing the meeting dynamics better, calling out poor behaviour, etc.

While these might help, a much more useful approach is to focus first on the relationships. You might think of this like the Titanic and the iceberg - it’s what’s below the waterline that can sink the collaboration. And the relationship element is below the waterline; harder to see and trickier to deal with, but much more likely to allow smooth sailing when tackled.

Healthy collaborative relationships create a safer and more stable working platform in which to deal with current and emerging issues. So what can help reset the relationship and set you up for success in your collaboration?

- Acknowledging the history. Often there is baggage around what has happened before that impacts our behaviour, for example a past event that sticks in our mind and causes us to mistrust what others do. Surfacing some of that history and the consequences for each of us can help clean up the baggage. While this might be seen as opening old wounds, unacknowledged baggage can paralyse interactions, while respectful inquiry and acknowledgment in a safe environment can allow people to move on

- Checking and testing assumptions. Making visible our respective assumptions can be quite revealing, and allow us to test and explore the views we hold about others, and they about us. We can be quite surprised, and sometimes shocked (how could they believe that about us…..?), but we are then in a position test them and consider the implications for our work together. This can be quite cathartic, providing new insights and understanding of why people (us and them) may act the way we do.

- Putting yourself in the other’s shoes. This is where you try to see the world from the other person or group’s perspective. What really matters to them? What do they deeply care about? What makes them tick? What does their boss look for in their work? For example, one group might value social equity, and another may value technical expertise. If each perceives any situation only from their own perspective, misunderstandings and assumptions about motives might make it really challenging to find solutions together, leading to confusion and frustration. Taking time to hear how others think and work provides more shared understanding, facilitating more useful joint action on the difficult issues.

Sometimes clients are concerned that these activities will take time and distract from getting solutions. On the contrary, such reset activities can be a critical and essential investment in a robust working relationship, avoiding risks to solving key issues of structure, process and content. Is it time to reset your collaborative relationships?